|

Don't Miss a Beat: SUBSCRIBE on our Home page

|

|

8/31/2021 0 Comments Taking Stock of Stocks

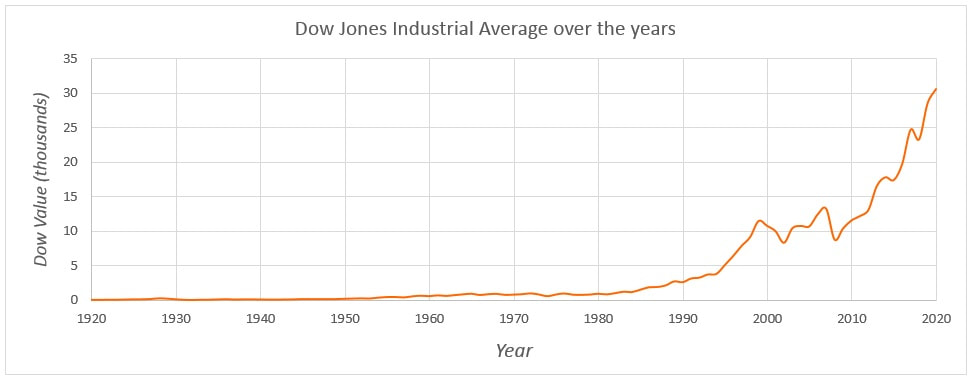

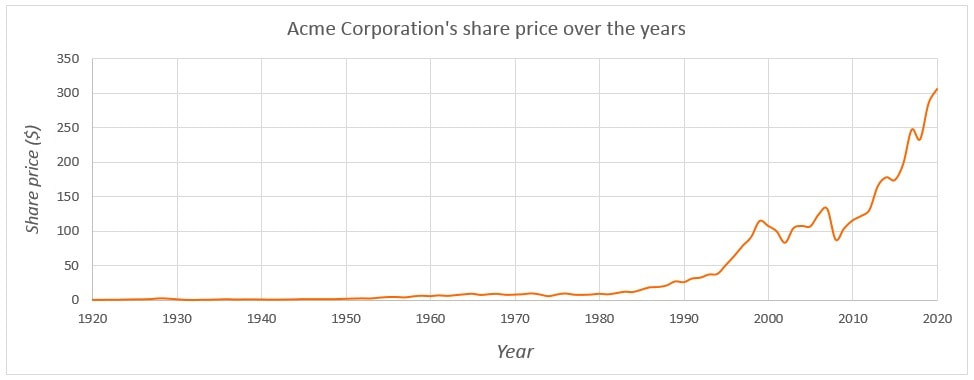

I’ll share with you why I think the way I do. But first…I need to kick this out of personal space. I don’t want any of my friends or loved ones to get sore about it. I’m not trying to convince anyone that they should do anything different. I’m just writing for the fun of it. So rather than rebutting anything that I’ve heard anyone say personally, I’ll cite some generic quotes that represent the usual chatter about the stock market: “Investing in the stock market can be a great way to grow your savings over time. ... You can reduce the risk of losing money by investing in multiple companies instead of a single company. A mutual fund can help you diversify your investments for low fees.” – TheSimpleDollar.com, Sep 2, 2020 "...It is generally better to hold stocks for the long term...preferably a decent amount of years. Holding stocks for short time periods is rather considered speculating instead of investing and will essentially increase your risk of losing money in the long run." – Cliffcore.com, Apr 29, 2021 “Stock market investments have proven to be one of the best ways to grow long-term wealth. Over several decades, the average stock market return is about 10% per year.” – NerdWallet.com, Jul 29, 2021 To me this smells a lot like advertising language. Just saying. * * * Now it could be that I’m just the suspicious type, someone who’s wired to be a little skeptical of bold claims. But then again, I could be right. There’s an old saying: “Believe only half of what you see and nothing that you hear.” As if proving the point, some claim it was Ben Franklin who said this, while others claim it was Abe Lincoln or Edgar Allen Poe. Some even attribute it to DMX. Jesus. I’m not saying “Jesus” because I think Jesus should get credit for the quote. * * * Anyway, all of the above turns into the following inside my head: I wonder what it would be like to follow the life of a hundred-dollar bill that’s stuffed into the stock market? A slice of blue cheese, as DMX would say. Wait a second. What if I ramble on too long, lose your interest and attention somewhere along the way? It could happen. It’s a risk. I have to remind myself that I’m writing for the heck of it. Not because I expect or deserve your time and attention. I think it’ll be fun. So here goes nuthin.' * * * The first thing that happens to our $100 is this: It leaves our pocket and lands in someone else’s. For the sake of argument, let’s assume there’s no brokerage fee, so our entire $100 is received by Acme Corporation, who in exchange gives us some “stock” in their company, which is just another way of saying they’re selling us a percentage of equity (ownership) in Acme. Let’s say that Acme is a big company, worth millions, so our $100 only buys us a tiny sliver of the Acme pie. We’re not going to get a reserved parking spot or an invitation to the company holiday party. We’re not going to being hanging out down at The Club with the Board of Directors. But here we are, nonetheless, with some stock (equity) in Acme Corporation, stock that we paid $100 for. Let’s say our $100 bought us one share of stock out of thousands of Acme shares. The next thing that happens is the responsibility of Acme. If Acme is a U.S. company, they’re supposed to say something to the IRS about the $100 they just received from us. If the entire $100 looks like company “income” to the IRS, Acme will have to pay something like $35 to the IRS in taxes. Ouch. Acme doesn’t want to do pay those taxes. Luckily, they have some ways to avoid this. One way is for Acme to simply call it “working capital” instead of income. Another way is for Acme to say that the stock they sold us was somehow valued at $100, such that, technically, there was no real gain (income) for them in the transaction. For our case, let’s say that Acme has a good accounting department, and they are indeed able to pocket our $100 without having to pay any taxes on it. Good on them! This means that $100 of our real personal wealth has been successfully transferred to Acme. [Side note: If you are a person instead of a corporation, and you try to raise some money for yourself, you won’t have any legal ways to escape from giving the IRS their cut. Only corporations have the luxury of raising money without it being a “taxable event” in the eyes of the IRS. People get into trouble with this kind of thing all the time on crowd funding platforms like Kickstarter and GoFundMe. They raise some money for a personal project or a worthy cause and then they’re surprised when the taxman comes knocking. D’oh!] Now back to our little $100 experiment: Acme has our $100 in their pocket to do with as they please. They have the potential to go on and do great things with it. We’re out our $100, but we now own one share in Acme Corporation. This share doesn’t grant us any significant ownership clout within Acme, but we’re totally OK with that. We’re in this because we like the idea of investing in Acme Corporation. We’re gonna be rooting for them. If Acme does well as a business, their share prices may increase over time. And then, one day in the future, we might be able to sell our one share of Acme stock for more than $100! * * * Let’s say Acme is a perfectly average company such that their company performance over time is magically identical to the stock market as a whole. When the Dow Jones Industrial Average goes up or down, Acme’s stock follows the same exact pattern. So what does the Dow Average look like? Historically, it looks like this (these are real numbers I snagged from Macrotrends.net): Pretty good right? A few little blips along the way, but basically onward and upward! Let’s go ahead and map this over to a fictitious share price at Acme so we can figure out what will happen with our $100 investment. To do this, let’s just convert the Dow Value into an Acme share price, but keep everything else the same. Here’s what we get: Acme is a perfectly average company, so this is what their stock value would look like through the years. Now let’s pick a time in the past and pretend that’s when we made our $100 investment. To keep things easy, let’s say we made our investment exactly 20 years ago in the year 2001. As you’ll see from the share price chart, Acme’s share price in 2001 was … $100 per share. That works out nicely! We don’t have to do any fancy math or anything. What we’re interested in, of course, is our “return on investment.” We spent our original $100 back in 2001, and since then we’ve only had a piece of paper that says we own one share of stock in Acme Corporation – which isn’t really worth anything to us unless we can sell it to someone for some cash. And we’d love to sell it for more than our original $100 so we can make some profit. We’ve been advised (as with the 2nd generic quote up above) to play a long game with this stock market thing, rather than being speculative and trying to make a quick buck. So let’s imagine we’ve held onto our stock for a solid 20 years and we’ve decided that the time has finally come to sell it, this year, in 2021. * * * So we sell our stock. We can’t really sell it ourselves since there’s no mechanism for a private person to buy or sell stuff on the stock market, so we’ll need to do this through and agent or broker. But for the sake of argument (and as was the case with our original purchase), let’s assume there’s no brokerage fee. Here’s the great news: According to the chart above, today in 2021 our single share of Acme Corporation stock is worth $306! This feels like a win. It feels like we’ve beat the House. We surfed the steepest part of the money-making curve in the entire history of the stock market and we’ve tripled our money! Unfortunately, there’s a little catch. Although we do indeed stand to get paid $306 dollars for our share of Acme stock, we need to do some reckoning of how much profit will actually go into our pocket. The first thing to realize is that our original investment left a $100 hole that needs to be filled before we can start appreciating our win. So let’s pay ourselves back that original $100. That still leaves us $206 in “winnings.” No problem. $206 is still pretty darn good! Then there’s a matter of taxes. The IRS will look at that $206 as income (a long-term capital gain, to be specific), and they’ll want to snag 15% of it. That’s assuming our other income doesn’t exceed something like $450k per year – in which case they’ll want to snag 20%. Fifteen percent of $206 is $31. So we’re left with $175, and that’s still not a bad profit, right? Unfortunately, there’s one more tax to consider: Inflation. Not many people refer to inflation as a “tax,” I realize, but it definitely is one. How do we take this into consideration? One way to make sense of inflation is to jump back and forth in time a couple times. Basically, we need to figure out our buying power today compared to 20 years ago. Let’s imagine we “invested” our $100 bill by simply sticking it inside a shoe-box under our bed back in 2001 and then we went to sleep for 20 years, just like Rip Van Winkle. When we wake up and retrieve our money in 2021, we’ll find out that we can can’t buy as much stuff with $100 as we could have back in 2001. And it’s stuff that has real value, not cash. Cash, in and of itself, is just a convenient medium of exchange that people have cooked up. What I mean is this: A $100 bill doesn’t really mean anything to us until we exchange it for real things – until we exercise its buying power on food, clothes, shelter, toys, books, gasoline, etc. It’s kind of like our Acme stock in a sense – it doesn’t have any real value to us until the moment we decided to trade it for something else. So to figure out what we’d like to call “profit” (which is really our increase in buying power), we have to travel back in time to 2001, to the time when we originally spent our $100 on Acme stock, and then imagine what it would feel like to take a 20-year nap and then find $275 in our shoe-box – that’ll be our original $100 plus the extra $175 we figured out up above. Here are some interesting numbers that can help us do that (I grabbed these from Statista.com):

There’s a ton of other prices we could study and compare. What we’re after is a rule of thumb that says “In 2001 if the average cost of something was $100, in 2021 that same something would cost us ______.” Based on the above car price and movie ticket price (and as many other things that we might wish to include to feel confident) we know how to fill in the blank! The answer is $177. Another way to say it: Things are 1.77 times more expensive now than they were 20 years ago. That’s inflation. So let’s put this up against our $100 Rip Van Winkle shoe-box investment and see where we come out. * * * Remember, we’re imagining being back in 2001 and we’re about to take a 20-year nap and find our original $100 bill plus an extra $175 in our shoebox – so $275 in total. Based on what we just figured out about inflation, when we wake up we’ll need to bolster our original $100 in order to give it the same buying power that we’d expect. That original $100 will need to become $177 in order to be able to buy the same amount of stuff 20 years from now. We can do that! We have it covered! We’ll simply take $77 dollars from our extra pile of dough and set it on top of our original $100 bill. That makes our original $100 whole again in terms of its buying power. Our extra pile of cash goes from $175 down to $98. That $98 is the amount of new buying power we’ll have in 2021. It’s the real amount of extra cash we’ll have in 20 years. No strings attached – we’ve considered taxes, inflation, etc. There’s nothing more to chip out of that $98. That feels OK to us so we’re just about to pay our $100 and get our Acme Corporation stock. We’ve thought this through. It’s clear to us now that we’re not going to “triple our money,” but is sensible to imagine that we’re going to pretty much double it? Not quite. There’s one more thing. We can’t directly compare new money to old money. It’s apples and oranges. Let’s stretch our imagination a little further to picture ourselves handing our $100 bill to Uncle Pennybags (you know…the little Monopoly guy), and he’s telling us what he’s going to do for us, how he’s going to make us rich in the stock market. Uncle Pennybags says, “Give me your $100 now, and in 20 years I’ll give you $306.” He’s not lying to us. But we’re wise to the game. We’d be deceived by this claim if we didn’t fully understand it. We’re most of the way there already. And here, at long last, is the final piece of the puzzle: If we really want a crystal-clear, non-deceptive promise from Uncle P, what would it look like? Should he say to us, “Give me your $100 now, and in 20 years I’ll give you $198,” instead of describing it as $306? That’s a little better, but it’s still not quite as clear as it needs to be. That extra $98 dollars he’s offering is future money. It doesn’t completely make sense to our 2001 ears because that money won’t have as much buying power as our 2001 money. From our 2001 perspective, based on what we reckon we can buy with our money now, that $98 in future money will feel like about $55 to us. Why do I say this? It’s based on our inflation rule of thumb that we worked out up above, where we would say, “In 2001 if the average cost of something is $55, in 2021 that same something would cost us $98.” So if we’re after the unsalted truth, here’s what Uncle Pennybags should be offering us: “Give me your $100 now, and in 20 years I’ll give you $155.” Now, would anyone hand over a $100 bill to Uncle Pennybags based on that? Well, I guess some people might. But to me, it sounds like a pretty crumby investment. He’s asking us to tie up $100 for 20 years, and he’s only offering us 2.35% interest on it. (That’s the simple interest rate that would grow our $100 into $155 over 20 years.) * * * For most stock market investors, I think the reality is actually even bleaker than what I’ve described above as a paltry 2.35% return. Why do I say it’s bleaker? Three things: Brokerage and/or money management fees, opportunity costs, and the creatures called “mutual funds.” I promise I’ll be quick about this. I’ve already wind-bagged you plenty. Up above we assumed there were no brokerage fees associated with buying or selling our Acme stock. But we both know there would be some fees involved. That’d be another little scrape off the top. Also, we might be working with a financial advisor, someone who’s “managing our investment portfolio.” They’ll take a scrape as well. Usually these types charge an annual fee that’s some percentage of the total value of our investments. That can add up to quite a lot over, say, 20 years. And if we’re working with a financial advisor, it’s likely that we’ll find ourselves investing in mutual funds rather than individual stocks from individual companies, like our Acme example. Mutual funds can be riskier than people realize. I’ll say a little more about them in just a second. And above all else, tying up our $100 for 20 years means that we’re not able to use it for anything else. This could result in some missed opportunities to use or invest our money more wisely. A brief ramble about mutual funds: Investing in a mutual fund is kind of like investing in a middle-man company that spreads their own investment money across stocks, bonds, short-term debt, and other stuff. A mutual fund refers to its collective investments as its portfolio. Fundamentally, a portfolio is attempting to be diverse and therefore less volatile than any single stock would be, and the hope is to hit a performance target that’s related to the Dow Average. An “aggressive fund” will try to beat the average on the upside, and a “conservative fund” will try to stay down below the radar as the Dow goes through its usual ups and downs. The main game of any financial advisor or “wealth management consultant” is to set you up with aggressive funds when you’re younger (in hopes of snagging you some wins) and then shifting you toward more conservative funds as you get older (to protect you from big losses). But here’s the thing: If we buy a share in a mutual fund, we’re actually buying into the value of a pre-packaged portfolio, and that’s different than investing directly in company shares. For example: There’s only a finite number of shares available in any company. But most mutual funds are open-ended, which means they will issue as many shares as people want to buy. (Now, there are such things as a closed-end mutual funds where this isn’t the case, but these aren’t the common variety.) Without going down another rabbit hole, here’s the end result of this “open-ended” approach to issuing shares that’s baked into most mutual funds: It creates a disconnect between a $100 investment that makes it harder to realize gains. That’s because the value of our shares in a mutual fund portfolio – which are just shares in an infinite pool of available shares which can be created willy-nilly – is sensitive to percentage gains and losses of the portfolio, rather than any absolute, price-per-share value assessment. And when it comes to percentages, it’s way easier to lose money than it is to make it. Quick example: Let’s say we have a $100 investment in a perfectly diverse mutual fund and the overall stock market experiences a 25% drop. We take a hit and we’re suddenly down to $75. The next day, the market rebounds and then some – There’s a 30% gain. Hooray! Although it seems like we’d come out ahead in this situation, unfortunately we’ve actually lost some money here. That’s because a 30% increase on our $75 is only $22.50, so we’ve only gotten ourselves back to $97.50. Looking at the 2-day performance of the market, people would say that the market went up + 2.5%. They would be correct in saying so. That’s the average of +30% and -25%. But we just lost 2.5% of our money as the market went up by that same amount. What’s up with that?! OK, what if it was the other way around, you ask? What if we experienced a 30% gain on the first day and then took a 25% hit on the second day – surely that would work out better, right? I’m afraid not. If our $100 goes up 30% on the first day, we’ll be at $130. So far, so good. Then our 25% loss on the second day becomes … $32.50. So here we are at $97.50 again. Drat. Such is the case with many a mutual fund. It’s like a ratchet wrench that’s set to loosen rather than tighten. * * * There you have it. Investing in the good ‘ole stock market isn’t nearly as attractive as it might seem at first glance. If you come out unscathed and are lucky enough to have investments with average performance over the long haul, you’ll barely eke out ahead of cost of living increases. Of course, you could stay away from mutual funds and you could choose a hot stock that performs way better than our Acme example – way better than average. You could find the next Amazon! But I’d say you’d have to be pretty darn lucky (or well-connected) to land in that paydirt.

– O.M. Kelsey READ PREVIOUS BLOGS

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorO.M. Kelsey Blogs by Month

June 2024

Blog Categories

|

All content herein is Copyright © Chiliopro LLC 2020-2024. All Rights reserved.

Terms of Use Privacy Policy

Terms of Use Privacy Policy